The walls of HOTEL de L’ALPAGE are adorned with paintings throughout its interiors, reflecting the charms of a French house, where artworks are a staple on the walls, seamlessly blending into the atmosphere as if they have always been there. Each painting in the hotel has been carefully selected by the owner to evoke this familiar and timeless ambiance.

Experience how just one painting can transform the mood and atmosphere of a space, bringing the essence of an “art-filled environment” to life.

In this issue, we would like to introduce the paintings adorning the guest room-floor corridors of our intimate 12-room auberge.

Upon exiting the elevator on the second floor, the first work to capture the attention is a drawing titled “View of Rome, the Vatican”.

Although the artist remains anonymous, the piece is rendered in the distinctive style of the French painter Hubert Robert. Renowned for his depictions of authentic architecture, ancient ruins, and imagined monuments, Robert is a celebrated artist of the veduta and capriccio genres styles.

Along the southeastern corridor, positioned above a chest of drawers, hangs “Venice, the Church of San Giorgio Maggiore”. Although the artist is anonymous, the work is based on a motif by Francesco Tironi, an Italian painter celebrated for his Neo-Classical vedute of Venice. The veduta genre is defined by highly detailed, large-scale depictions of cityscapes rendered with topographical precision.

While this particular rendition is far more rustic than the original and can hardly be called a copy, the very simplicity of this painting gives it a certain charm, making it an interesting piece of art in its own right.

In the 18th century, the “Grand Tour” became fashionable among Europe’s aristocracy and wealthy elites. Much like an educational journey today, young nobles were sent across the continent to cultivate their cultural knowledge and aesthetic sensibility. Venice was among the most popular destinations of the Grand Tour, and travelers often purchased veduta as souvenirs of their journey. In a sense, veduta served a purpose very similar to photography today.

On the wall beside Room 21 in the southern corridor, an 18th-century Italian work titled “Venice, Piazza San Marco.” is displayed.

This is perhaps the most familiar motif among Venetian cityscapes.

A distinctive approach to perspective in this painting becomes evident when comparing the height of the arcade arches to the scale of the figures. While the figures in the distance appear significantly smaller than the arches, those in the foreground grow to nearly half their height, with the central figures especially drawing the viewer’s eye. This creates a decidedly theatrical quality, as if the figures were actors positioned before a painted stage backdrop.

Consequently, the focus seems to oscillate between the square as the primary theme and the figures as the main subjects for whom the square serves as a stage.

Although it may be an overinterpretation of such a common motif as Piazza San Marco, the painting seems to invite a reflection on the essence of urban space and how a public square functions as a living stage within the city.

The above is a painting titled “Flower Basket”, displayed on the wall beside Room 26. While bouquets are a classical motif in still-life painting, they are often composed of a wide variety of flowers. In many works, flowers from entirely different seasons are rendered with meticulous realism, almost forming an idealized bouquet that could never exist in nature.

In contrast, this flower basket is characterized by a simple composition, featuring only roses and forget-me-nots.

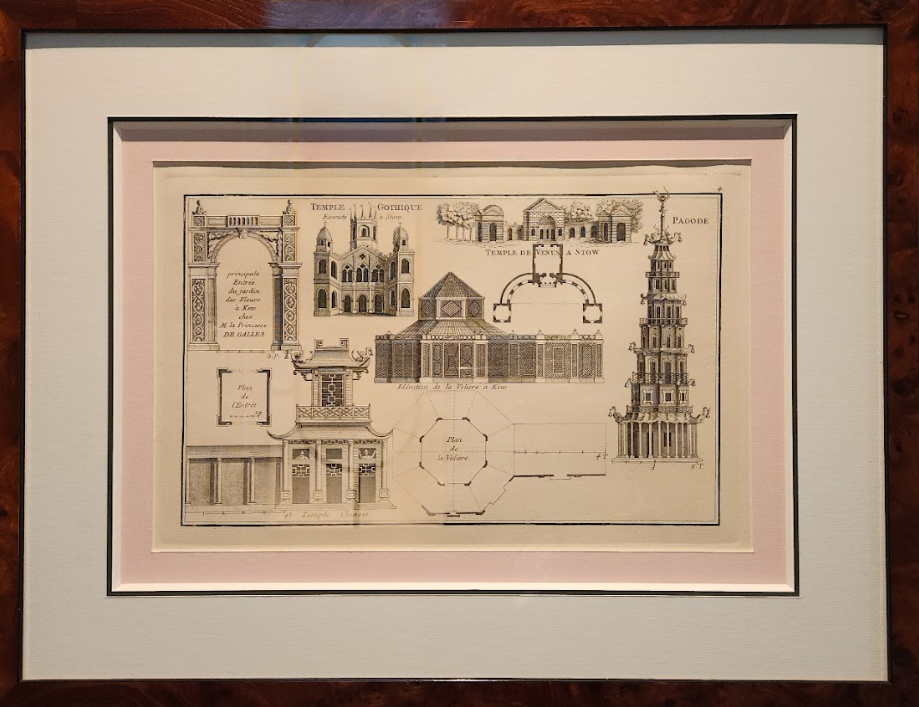

Among the paintings displayed along the second-floor corridor, the majority belong to a series titled “Details of a Fashionable Modern Garden: The Anglo-Chinese Garden”.

The works on display here are individual pages, framed separately before their final binding, from an 18th-century publication by Georges-Louis Le Rouge, a noted French cartographer, engraver, and architect. This series introduces different gardens from various regions, with a specific emphasis on the English-style gardens. The collection is composed of panoramic garden views, detailed ground plans, and architectural renderings of the various follies.

The English-style garden, also known as the “landscape garden,” is designed to imitate natural scenery. This style gained popularity after the era of the French formal garden, exemplified by the gardens of the Palace of Versailles. French formal gardens expressed the belief that the universe is governed by geometric order, with straight paths and trees meticulously shaped into precise forms, whereas the English style embraced the irregular beauty of nature. Yet this “nature” was often populated with a variety of follies, small architectural structures scattered throughout the landscape. The origin of the term folly does not derive from the notion of madness, but rather from simple shelters whose roofs were once covered with leaves (feuilles) or branches.

In truth, the ‘nature’ represented in these gardens was not a reflection of the European wilderness, but rather a curated scenery inspired by landscape paintings and capricci.

For example, in the 18th-century travelers often carried with them “Claude glasses“, small, handheld mirrors of darkened glass. By viewing a landscape reflected in these tinted mirrors, the viewer could see the world as if it were a canvas painted by the renowned Claude Lorrain.

For this reason, English-style gardens were populated by an array of follies: Chinese pagodas (chinoiserie), Egyptian pyramids, Greek and Roman temples, and even artificial waterfalls or fabricated Gothic ruins.

These landscapes could be described as a manifestation of the world of chinoiserie into a garden. Ultimately, they were an expression of excessive taste; or perhaps they could have even been a form of madness, a true ‘folly’ in every sense of the word.

By walking through such a landscape, a visitor could experience a condensed journey around the world, at least as it was imagined at the time. In this sense, these gardens functioned as an early precursor to the modern theme park.

In our Library Bar, a reprint of Le Rouge’s work is available, allowing guests to view the complete collection of “Details of a Fashionable Modern Garden: The Anglo-Chinese Garden” and fully immerse themselves in the architectural fantasies of the 18th century.

While the second floor features a cloister-style layout that allows guests to walk the full length of the corridor in a continuous loop, the third floor adopts a U-shaped configuration. Here, the central wall gently projects at an angle, and freestanding floor lamps are placed along the path, creating the atmosphere of an attic.

Along this distinctive third-floor corridor another series of drawings is displayed.

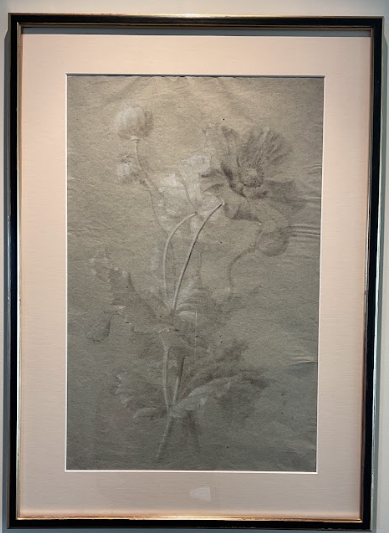

Most of the works on display here are botanical studies and practice drawings by anonymous artists. While we often associate drawing with charcoal or pencil on white paper, these pieces are created on a gray ground, utilizing pencil with highlights added in white chalk.

This choice of gray paper gives the painting a calm and subdued tonality. Moreover, the application of white is particularly distinctive. On traditional white paper, highlights are simply the absence of marks-areas left untouched, on colored paper, white is a deliberately added element. Even when the visual brightness is the same, the artistic sensibility required to apply white with chalk is different from leaving white via the paper. Though these are modest studies, they invite closer inspection through this subtle approach of expression.

Simonti atelier Deglane

At the junction where the western and southern corridors meet hangs a large-scale drawing with pencil and colored with watercolors. Its true subject remains a matter of debate: some suggest it was a proposal for a lakeside casino, while others identify it as a design for the 1900 World Exhibition. Regardless of its origin, it represents a project that was never realized, and the depiction of the boats suggests a scene far removed from reality.

Ultimately, the painting invites the viewer to imagine how delightful it would be if such a building or landscape truly existed. It serves as a reminder that art does not need to always represent reality; rather, it can exist simply as a vessel for the imagination.

Positioned at the far end of the north corridor on the third floor is a drawing by a French painter active from the late 18th to the early 19th century. Primarily a painter of portraits, landscapes, and scenes of everyday life, his work is characterized by a realist approach influenced by Dutch painting. This is most evident in the masterful use of light and shadow, and a meticulous attention to architectural details.

The drawing on display, “Sainte-Foy near Lyon”, serves as an example of these stylistic qualities and stands as a representation of the artist’s manner.

In this article, we have introduced a selection of the paintings displayed on the guestroom floors.

From the architectural design of the corridors to the genres of the artworks on display, the second and third floors each offer a distinctly different atmosphere.

Explore the building and discover the paintings displayed throughout the hotel, immerse yourself in an atmosphere that evokes the elegance of a private French residence.

This concludes Volume 5 of our “Spaces with Painting” series. To learn more, we invite you to explore the previous editions:

・View Vol. 1 here

・View Vol. 2 here

・View Vol. 3 here

・View Vol. 4 here